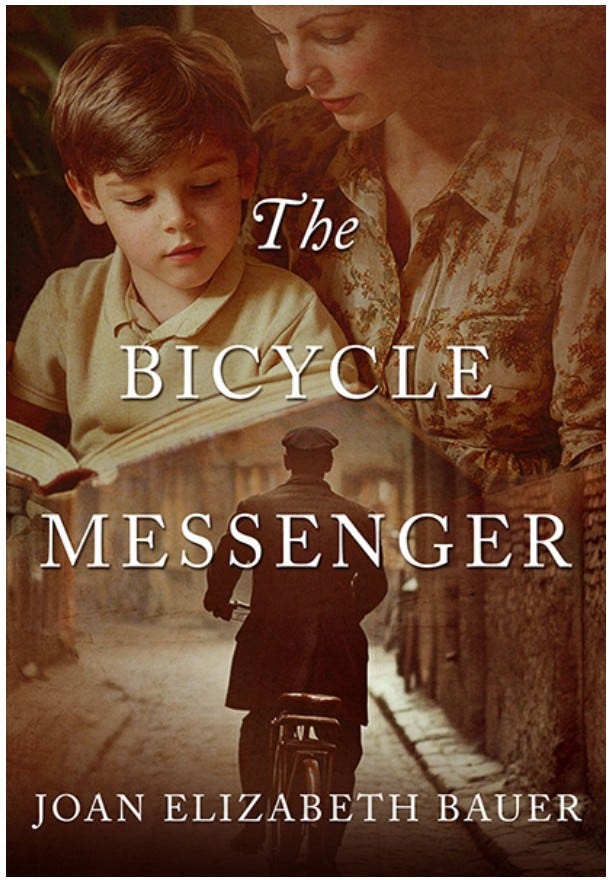

One more sneak peek at The Bicycle Messenger

Aug 01, 2025

It’s almost here! The Bicycle Messenger releases in just a few days! I can’t wait to share it with you. In the meantime, here are three takes on baptism in the story.

- Seven-year-old Steven Hawley is conditionally baptized because no one can locate his baptismal record. For the rest of his life, Steven wonders whether his baptism really “counts.”

- Steven’s mother agonizes in her uncertainty as to whether her grandson, who died in infancy, was ever baptized. Will she meet him in heaven, or will he spend eternity in limbo? Where is God’s mercy in this?

- In 1942, a Catholic priest proposes to rescue a Jewish child from the Kraków ghetto in Nazi-occupied Poland. Speaking to the child’s devout Jewish grandfather, the priest says, “if we do not baptize them, they will never survive. They must believe themselves to be Christians if they are ever to pass outside these walls.”

A few words on the Catholic Church in the Nazi Era

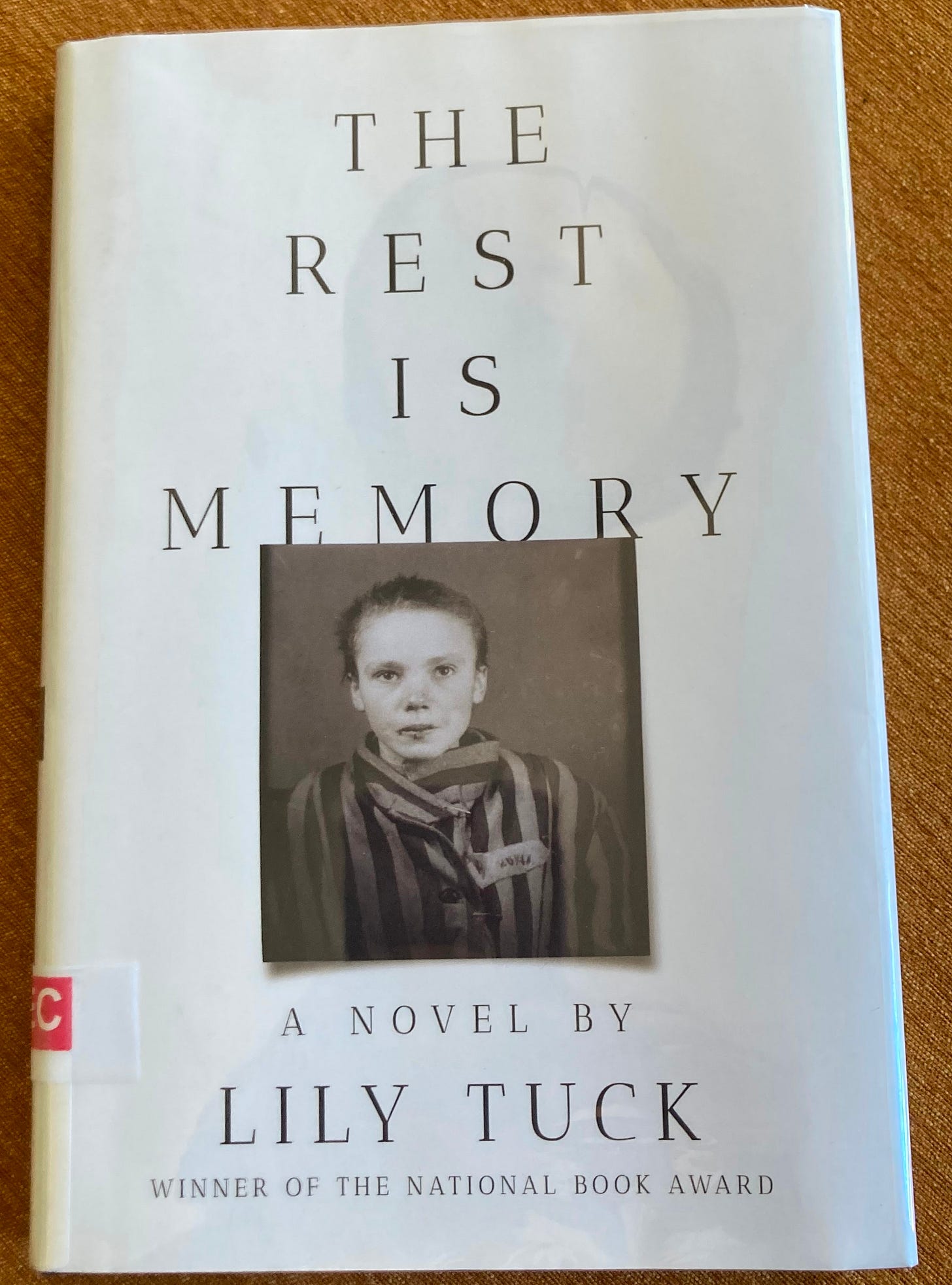

In her hauntingly beautiful novel of a young Catholic girl who perished in Auschwitz, author Lily Tuck cites Ronald Modras on the state of Catholicism in Nazi-occupied Poland:

During the German occupation, the Polish Catholic Church was in disorder. The Germans killed several thousand priests. In Rome, Pope Pius XII offered little support, instead advocating compromise with Germany. The Polish primate, Cardinal Hlond, had left Poland and had taken refuge in a Benedictine abbey in Savoy, France, and did not offer spiritual aid to his parishioners. Instead, in a 1936 pastoral letter, Cardinal Hlond wrote condemning the Jews: “It is a fact that Jews are waging war against the Catholic Church, that they are steeped in free-thinking, and constitute the vanguard of atheism, the Bolshevik movement, and revolutionary activity. It is a fact that Jews have a corruptive influence on morals and that their publishing houses are spreading pornography. It is true that Jews are perpetrating fraud, practicing usury, and dealing in prostitution.” (56-57)

These are painful words to read. They do not anticipate that a future great saint and Polish pope will undergo his priestly formation in secret under Nazi occupation; they do not anticipate that St. Maximilian Kolbe, arrested shortly after receiving his brilliant insight into Mary’s announcement at Lourdes—I am the Immaculate Conception—will serve the prisoners of Auschwitz faithfully and in secret as priest and confessor, ultimately offering his own life in exchange for that of a man condemned to the starvation bunker.

But while individual members of the church are prone to sin, the truth of the Catholic faith springs from the person of Jesus Christ. As Thomas Merton writes in New Seeds of Contemplation,

the living Tradition of Catholicism is like the breath of a physical body. It renews life by repelling stagnation. It is a constant, quiet, peaceful revolution against death. … only a gift of God can teach us the difference between the dry outer crust of formality which the Church sometimes acquires from the human natures that compose it, and the living inner current of Divine Life which is the only real Catholic tradition.

Getting back to the question of baptism

As I have noted before, there were many acts of specifically Catholic witness during the Holocaust. In her 1986 book When Light Pierced the Darkness: Christian Rescue of Jews in Nazi-Occupied Poland, Nechama Tec takes a scientific approach to such acts, collating data from numerous personal interviews in order to arrive at a realistic picture of the often-fraught relationship between rescuers and survivors. She tells of one devout Catholic Pole who struggled to reconcile his compassionate impulses with the anti-Semitic sermons he was hearing in church: “‘I am sure to lose both worlds. They will kill me for keeping Jews and then I will lose heaven for helping Jews.’” (146)

Tec makes it clear that not all rescuers intended to rescue anyone; many had their Jewish charges thrust upon them, one way or another. But for members of religious orders or the clergy who set out to rescue Jewish children, the question of baptism takes on cultural and spiritual urgency.

Were Jewish children baptized and saved because the Church wanted converts? Or were these children raised as Catholics because this gave them a better chance to stay alive?

Or both?

In other words, did we baptize them in order to save them — or did we baptize them in order to save them?

While admitting that children accepted into a Catholic institution were baptized, Dunski [a devout Catholic rescuer] said that this was done for safety. By becoming baptized[,] Jewish children saw themselves as Christian and therefore could more easily adjust to their new identity. … Young survivors I interviewed mentioned the comforting and soothing effect that the Catholic religion had upon them. … [T]here are many cases on record showing reluctance to baptize these children without the permission of their Jewish guardians. (141-142)

In writing The Bicycle Messenger, I was intensely drawn to the conflict within the soul of a man who knows that the only way to save a child in his care is to offer her into the hands of a priest whose creed he does not understand. As for the child’s mother—well, if you want her side of the story, you’ll have to read the book.