On the books I choose, and those that are chosen for me

Nov 29, 2025

For years, I have chosen my books from my husband’s admittedly rarefied shelves. It was in his collection that I first discovered the worn-out volumes of Proust that I consumed over my lunch hour at work in my mid-twenties. This was right after graduate school, and I was struggling to adjust to my new secretarial job. One day, a man I didn’t know approached me in the employee cafeteria of our venerable Milwaukee bank, nodded at my book, and asked if I would recognize the bank president on sight. When I asked why, he informed me in all seriousness that reading was not allowed here in this cafeteria; employees were expected to socialize over lunch, and the formidable Mr. P. was known to drop in unannounced. I knew no one there with whom I might socialize, and I was too astonished to thank him for the warning. From that day, I ate my peanut butter sandwiches undisturbed with my book in Cathedral Square Park or at the Grand Avenue Mall.

It took me nine months to read all seven volumes of Proust; I bogged down along The Guermantes Way (book three). But the payoff at the end of that volume—when the Duc de Guermantes howls at the Duchesse to go inside and change into her red shoes at a critical moment—was worth every political disquisition I had to slog through. Around that same time, I consumed volumes of Balzac and Flaubert, Eliot and Gaskell, Brontë and Collins, Wharton and James, along with Wallace Stegner and Norman Maclean (it was the nineties). By the time we had children, my reading expanded in all sorts of beautiful ways: Beatrix Potter and A.A. Milne, Virginia Lee Burton and Johnny Gruelle, Richard Scarry and Eric Carle… you know the list.

But then reading turned social.

My husband says he could never join a book club—at any given time, he’s already working his way through some two dozen titles. And I almost said no when a group of my oldest friends invited me to join their book club in the early 2000s, because I cherished my unfettered reading habits too much. One founding member called and insisted that they didn’t want to do it without me, so I said yes. And I didn’t regret it. We spent many lovely evenings at book club together, and when she died in 2009 after a long illness, I asked her in my heart to take my intentions with her to heaven. May she rest in peace.

Book clubs have taught me a lot about surrender. There’s an element of sacrifice, even abandonment in committing to ten or twelve titles a year that others will chose; at an average of ten hours a book, that’s at least one hundred hours of “spoken-for” reading. Many of these books have been gems that I wouldn’t have found otherwise; I first read Kurt Vonnegut and Lois Lowry, Kristen Hannah and Anthony Doerr as book club selections. Even the books that I didn’t enjoy have taught me a lot about craft. Still, I’ll never get back the time I spent reading that singsong-y book about the mother who cuts huge swathes out of the map as impossible places to raise her dysphoric child—the one whose counselor bounces on an exercise ball and talks just like Pee Wee Herman. And I feel sorrowful when I can’t jump into a highly anticipated book because I’ve committed to reading something else for a book club.

So, why do I do it? Am I just looking for social connection—or is there something profound in setting aside my self-will and accepting the preference of another? A book that is chosen for me might be a gift, or it might be a cross that I need to accept; it might be an occasion for discipline, or an instance of “Thy will be done.” When I was younger, I roamed freely over the shelves, pleasing myself. Now, when I read a book that is chosen for me, I am pleasing another—perhaps even serving her, if together we can enjoy the book more or perhaps notice the dangers it might present. Mostly, in reading and talking about it with her, I am giving myself. That’s important to do when my natural impulse is to turn away from conversation in favor of reading. There is something unhealthy for me in being left to my own devices—literal and figurative—for too long.

And so, I can sorrow over all the things I haven’t read, or I can take delight in the book I am reading right now; I can try to compete with the person who’s read more than me, or I can profit from their careful reading of a text I do not know; I can hoard my own choices, or I can humbly accept a recommendation from someone as an offering of their inner life, an invitation to share something they have enjoyed. And I do believe that certain books rise to the top of the pile when God wants us to read them.

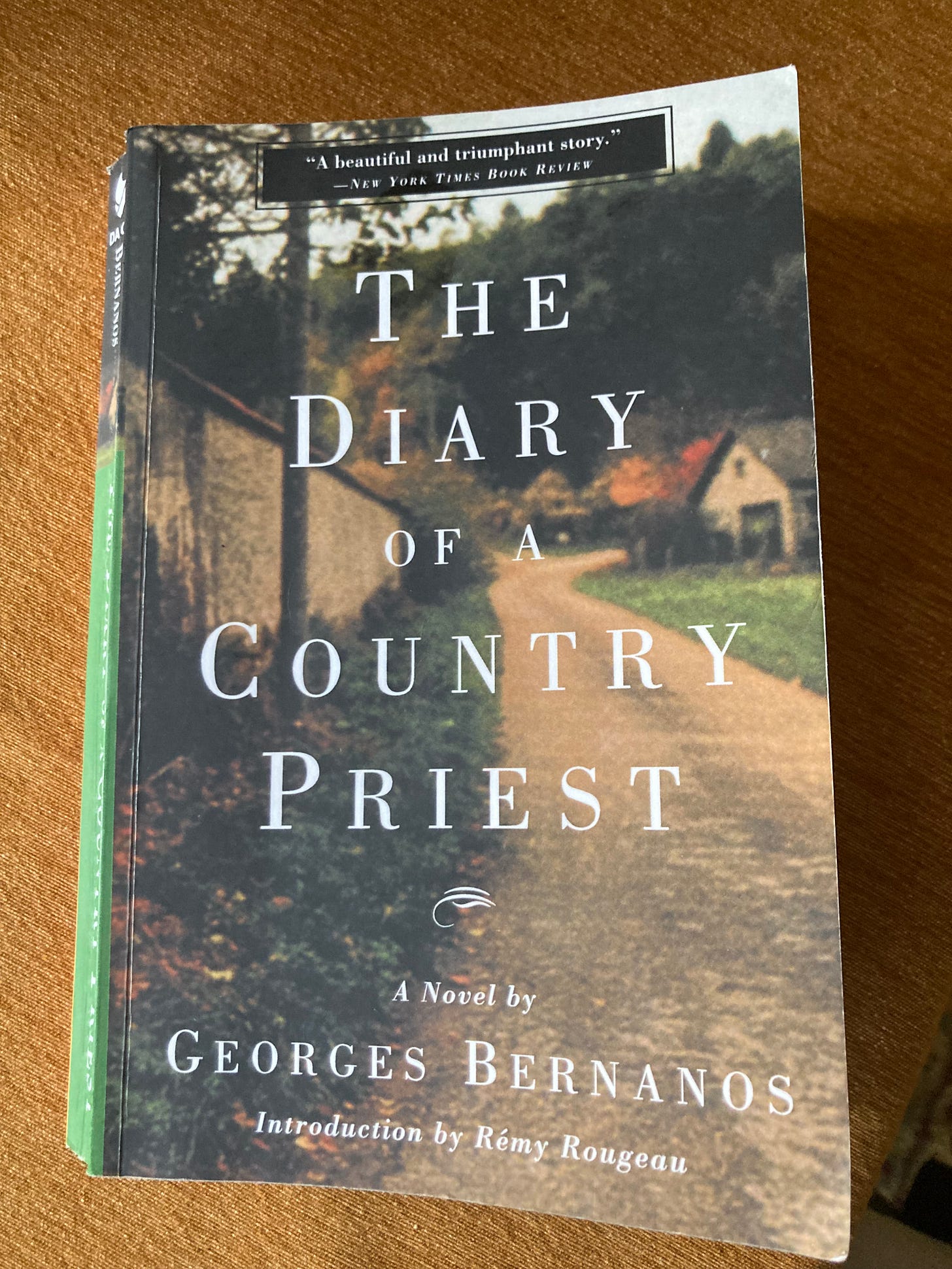

I had added George Bernanos’s The Diary of a Country Priest to my list at least three years ago, but when Dana Gioia mentioned in a podcast that certain critical passages had been restored in the 2002 edition, I was eager to start. Turns out, my husband had purchased the most recent edition earlier in the summer and was already partway through. (I can’t always keep track of what’s in those rotating stacks of his.) I had to wait my turn before we could start our own two-person discussion, but the payoff was every bit as wonderful as he promised it would be.

Early on, the unnamed young country priest of the title recalls his exposure to vice as a lonely, neglected child. He turns fruitfully to Russian literature for solace, particularly Maxim Gorky’s My Childhood:

There’s some of everything in it, as they say. The howling of a moujik under the rods, the screaming of a beaten wife, the hiccup of a drunkard, and the growlings of animal joy, that wild sigh from the loins—since, alas! Poverty and lust seek each other out and call to each other in the darkness like two famished beasts. No doubt I should turn from all this in disgust. And yet I feel that such distress, distress that has forgotten even its name, that has ceased to reason or to hope, that lays its tortured head at random, will awaken one day on the shoulder of Jesus Christ.

What a beautiful and hard-won depiction of divine mercy! The young priest carries deep wounds of abandonment and premature awareness of sin without sacrificing purity of heart; this rare combination wins him pastoral success, but at the steep social price of widespread condemnation. The text can be cryptic, as diaries are. I read some pages over and over just to get the plain sense of them. But the voice of the young priest quickly enthralled me. His strange diet of dry bread and warm, sugared wine leaves him indebted to unscrupulous tradespeople and subjects him to charges of drunkenness; his perhaps ill-advised tête- à-têtes with troubled young women—girls, really, who exhibit sophistication beyond their years—expose him to vilification by those whose consciences need to be pricked. He makes a pilgrimage of his prayer life, crossing vast deserts of dryness while bravely and tenderly admonishing sinners. This particular passage recalls Gertud von le Fort’s Song at the Scaffold, in which the fearful young novice Blanche de la Force takes the name “Jésus au Jardin de l’Agonie:”

Isn’t it enough that Our Lord this day should have granted me, through the lips of my old teacher, the revelation that I am never to be torn from that eternal place chosen for me—that I remain the prisoner of His Agony in the Garden. Who would have taken such an honor upon himself?

In the end, the young priest arrives at a pitch of forgiveness and renunciation worthy of any saint. The trouble with his life, he says, is that “there was no old man in me, ” and thus he has “loved without guile:”

And so I find great joy in thinking that much of the blame, which sometimes hurt me, arose from a common ignorance of my true destiny.

Of course, I can’t tell you about the payoff without spoiling the book, but it’s definitely worth it. “Grace is everywhere,” the young priest says. Even—perhaps especially—in a book someone else has chosen for me to read.

***

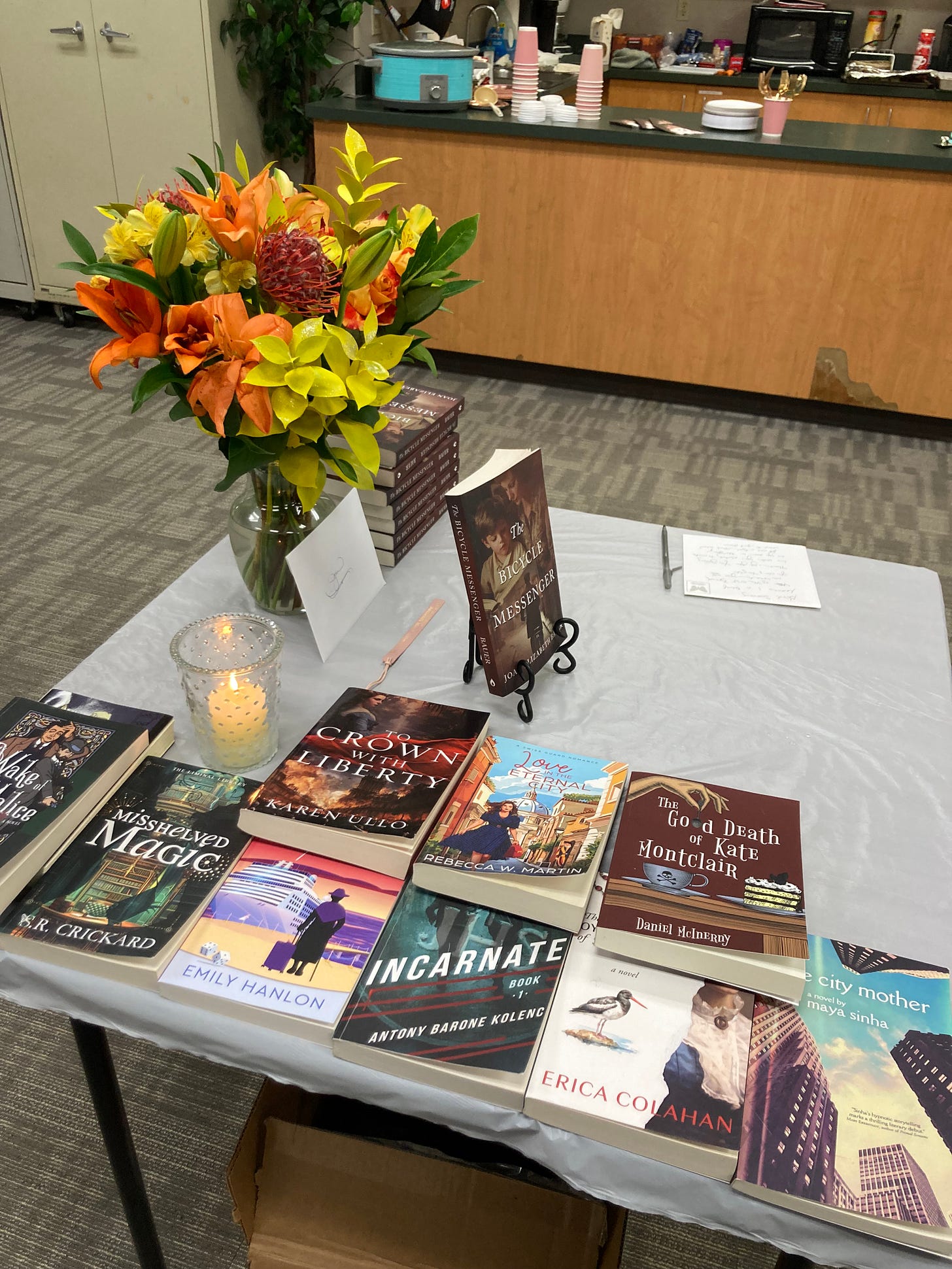

In other news, I had a wonderful time speaking to the Women of St. Jude on Tuesday, November 11 about my journey to publication. The delightful ladies pictured here created such a generous and hospitable atmosphere for all of us, complete with cider, charcuterie, and homemade desserts. In addition to reading from The Bicycle Messenger, I brought a number of Chrism Press titles for “show and tell.” As you can see, my collection is growing—my copies of the first two Molly Chase books are on loan, so they are not pictured. Everyone was very interested in the array of good Catholic fiction on offer.

I was also very pleased to learn that The Bicycle Messenger received the Seal of Approval from the Catholic Writers Guild. This designation assures Catholic readers and booksellers that the book will not offend their faith and that it is appropriate to promote in a Catholic setting. Thank you to the dedicated reviewers who provide this service through the Guild!