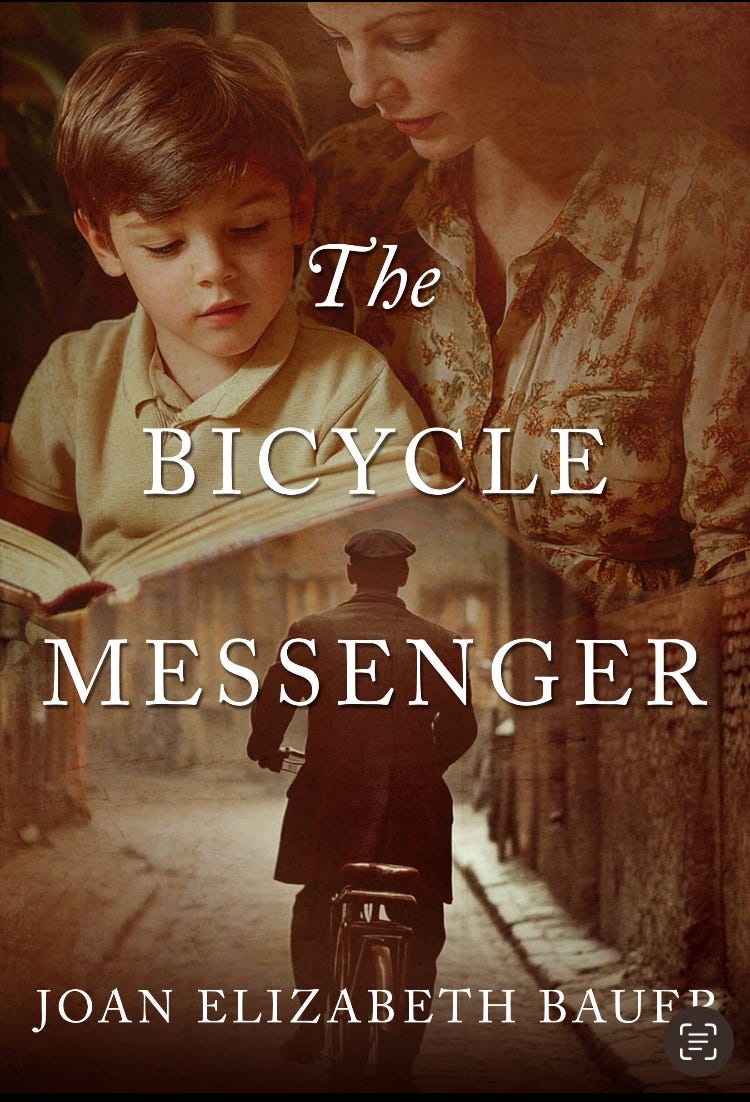

A real-life hero appears in The Bicycle Messenger

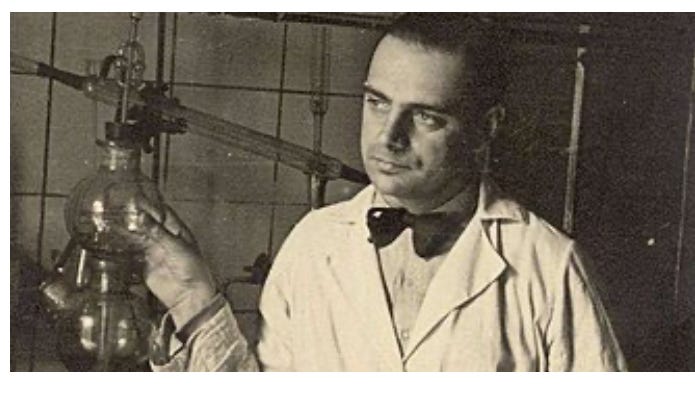

Tadeusz Pankiewicz (photo: Wikipedia Commons)

The Nazis established the Kraków ghetto in Poland in the district of Podgórze in March of 1941, initially cramming some 15,000 people into an area meant to house about 3,000. The previous residents of the district were evicted and given alternate homes or businesses. But one Roman Catholic pharmacist, Tadeusz Pankiewicz, refused to leave: “I understood only too well that the Germans would lose the war, and would destroy my pharmacy, and that I would have to return property that was not mine to its rightful owner or his family when the war ended.”

Pankiewicz was no ordinary man defending his property rights. His business, the “Pod Orłem” or “Under the Eagle” pharmacy, became a locus of communication and aid for the Jewish inhabitants of the ghetto until it was fully liquidated in March of 1943. Pankiewicz’s heroic witness and service to the Polish Jews in the Nazi era would prove to be of incalculable value.

In his memoir of the years he spent among the Jewish detainees, Pankiewicz writes with quiet compassion of the many gatherings he hosted and of the underground intelligence that passed through his pharmacy. “[E]very single room was full of friends, especially in the back rooms, whence it was easy to escape through the exit. It is hard to take in the fact that people managed to do it….” When the ghetto was divided in December of 1942,

The dividing line ran right in front of my pharmacy, which ended up in ghetto B. … [T]he inhabitants of ghetto B were all unemployed, generally poor people with nothing to live on. … They occupied empty flats and deserted buildings. Most of them had never been outside the village where they were born and they had never seen a large city in their lives before. … I tried to approach them to find out more about them, but they were like bears trapped in a cage, endlessly walking the length of the barbed wire fence and begging the passers-by in ghetto A for a piece of bread. … Many of them were barefooted, but it was the middle of winter, there was frost on the ground, it was cold indoors and the water in the pipes had generally frozen.

Pankiewicz received word in January of 1943 that the Germans intended to close his pharmacy, but he did not back down.

I presented my case and was given the necessary papers for the SS und Polizeiführer. I now had it in black and white—the closure of the pharmacy would have a detrimental effect on the health of the ghetto residents, and if the Jews were denied medicine, the ghetto would become a hotbed of diseases and epidemics which not even the ghetto walls or barbed wire could contain.

Pankiewicz’s Catholic faith plays a small but crucial part in the fictional Holocaust narrative embedded in The Bicycle Messenger—a narrative that will eventually illuminate many long-standing questions for the book’s present-day characters. In this brief exchange, a desperate young woman approaches Pankiewicz for a sedative for her mother, who has received a great shock:

My eyes filled with tears. The pharmacist reached across the counter and took my hand in both of his. He looked me right in the face, and then a change came over him. I was sure he remembered me because he looked from me to the baby in my arms.

“Does she cry a lot?” he asked.

“She has terrible colic.”

He nodded again, then he turned to search in the drawer behind him. “If the Gestapo come,” he said, “give her this.”

“What is it?”

“Just a small tranquilizer. It will soothe her so you can keep her quiet until they leave.”

An excerpt from The Bicycle Messenger containing this passage was originally published in Last Syllable. You can find it here or on my website, along with some of my short fiction and book reviews. I look forward to sharing the whole book with you August 4!