Actually, make that murder.

Dec 19, 2025

Last February, I joked that Milwaukee’s snow totals were finally catching up with Louisiana’s. Well, things have gone back to normal—we took our first hit of eight to ten inches on the Saturday after Thanksgiving. Most of that snow is still here*, plus whatever else has fallen since then (I confess I’ve lost track). The piles are slowly encroaching on usable driveway space, and the plow’s most recent leavings, now frozen solid, serve as makeshift speed bumps as we pull out onto the street.

But while winter has tightened its headlock a bit earlier than I expected, I haven’t really felt the need to escape. In fact, when we left town last week to attend our daughter’s college graduation in Florida, I worried about my unfinished Christmas shopping. A dear friend promised to drive by my house while I was gone and collect any packages that appeared at our front door—one of which spent a few days buried under the snow on our neighbors’ front porch, where they found it as they were shoveling on their return from a trip of their own. This is just normal, right? Why be a snowbird?

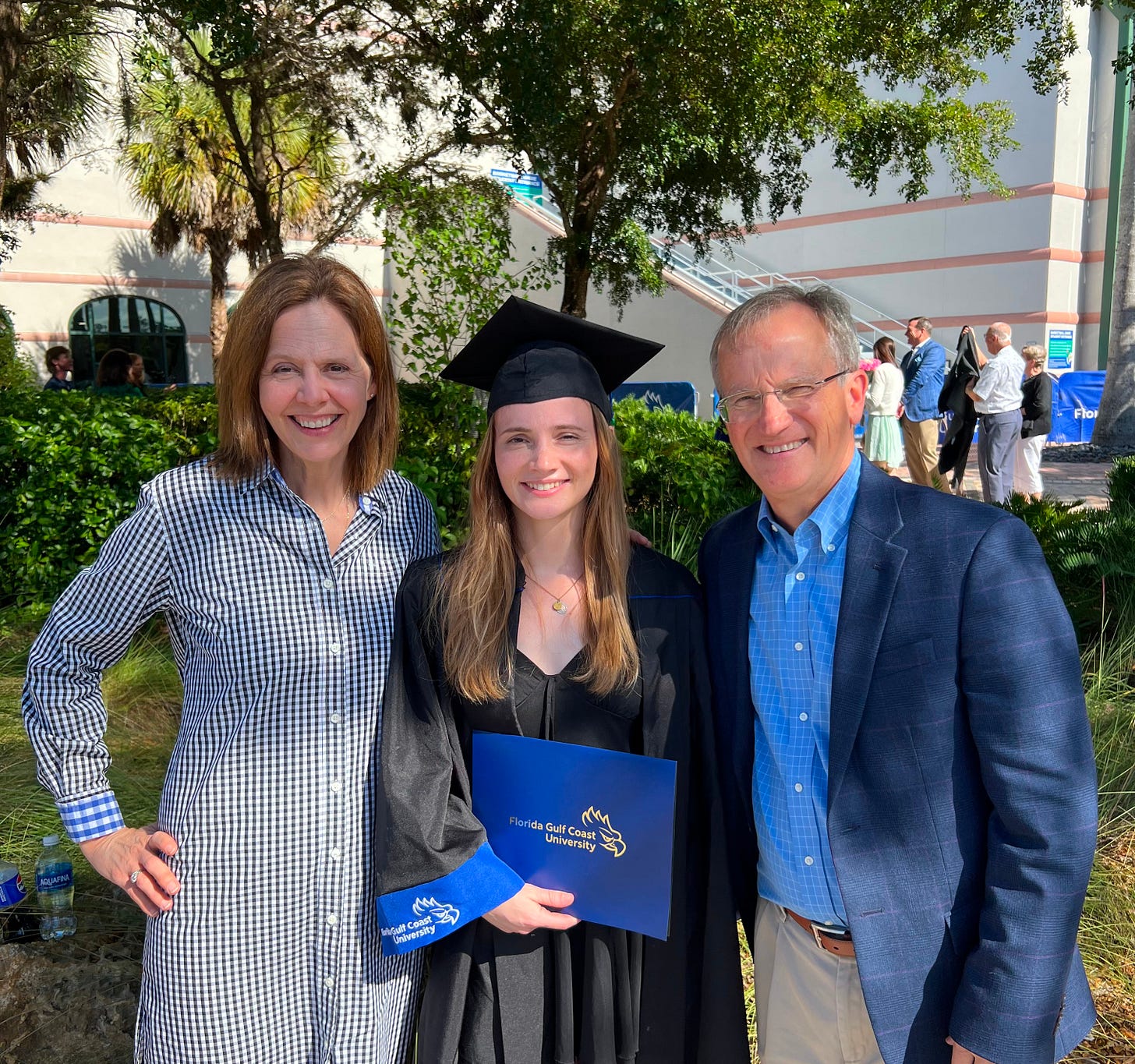

But the moment I stepped off that plane in Fort Myers, I understood. We shed extra layers under the palm trees, walked on the beach past the sandcastles of frolicking children, and ate ice cream outside after dark. We posed for graduation pictures under the bluest sky I’ve seen since September at least. Or maybe June. We’d landed in a meteorological sweet spot reminiscent of late spring, when the humidity hydrates you instead of oppressing.

Congratulations, Annie!

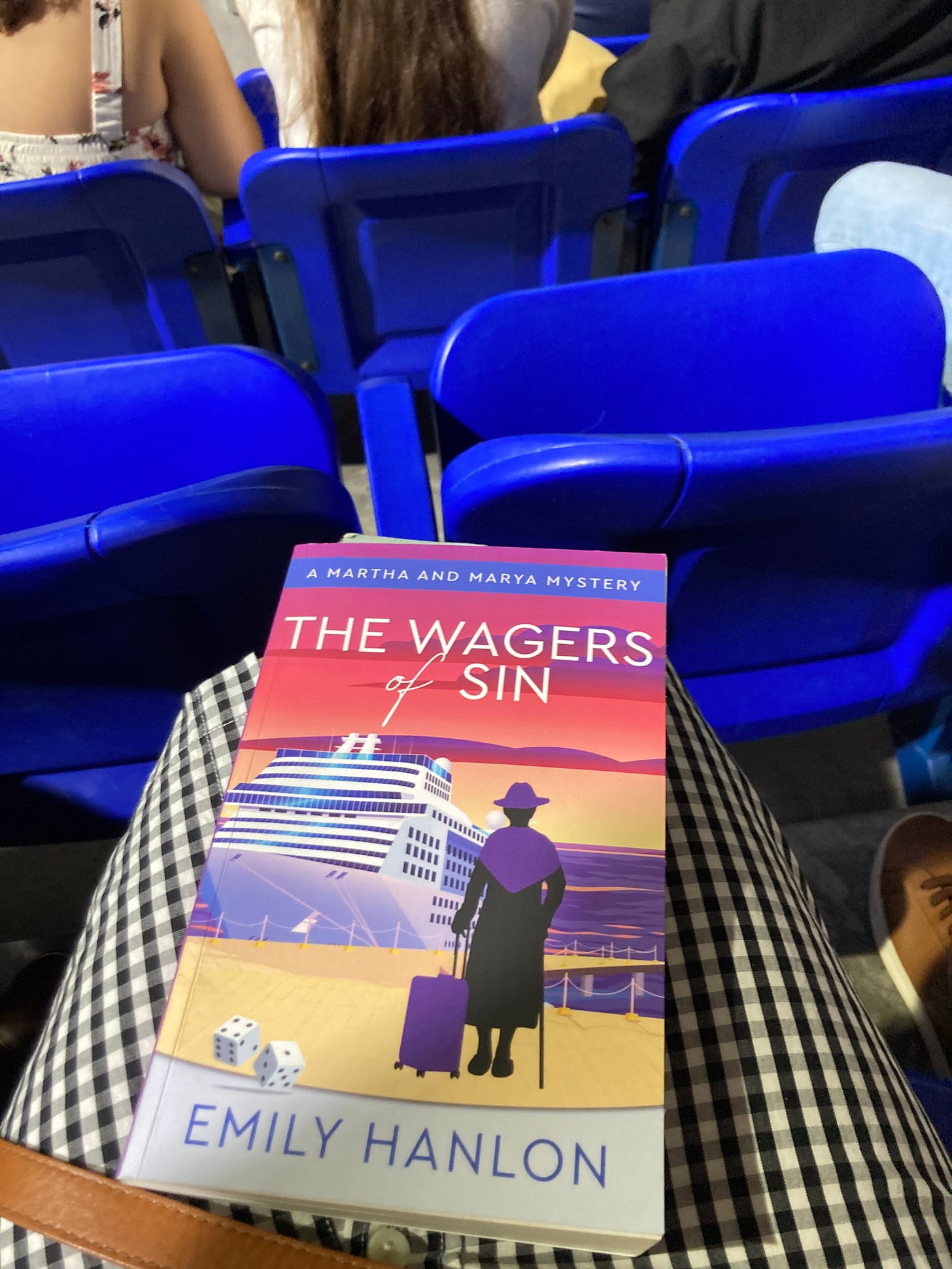

My husband and I brought books along to graduation because we’d had to drop our daughter off early. Before the ceremony, as two young women in long sequined dresses performed Ed Sheeran songs on the floor of the arena and pictures of smiling undergraduates cycled by on the jumbotron overhead, I was engrossed in the third installment of Emily Hanlon’s Martha and Marya mystery series, The Wagers of Sin. A young, handsome cruise ship employee was about to marry an elderly woman of enormous wealth. Helen Holmes, the octogenarian bride, had slumped in her wheelchair moments before pronouncing her vows when …

… the musicians cued Pomp and Circumstance, and several dignitaries began to process into the arena, followed by the graduates.

Darn it! I reluctantly put down the book just as Marya Cook—herself an elderly woman known locally as the “purple pest” —uses the word “murder” for the first time. Marya, who calls everyone “my dear” and quotes life lessons from a grade-school teacher named Sister Thomas More, commits occasional malapropisms while being a stickler for proper grammatical usage. Her friend Martha Collins tries to make ends meet as an Uber driver while running (without much hope of success) for lay commissioner of police. As you might expect, Martha is the more practical of the two. She is active in the Society of St. Vincent de Paul (we have that in common), and in lieu of swearing, she calls on an endless procession of little-known saints (“By the broken bones of Saint Sadoth, I am such an idiot”). Having successfully solved mysteries with Marya before, Martha follows Marya’s lead, though she rarely gets any credit.

The “wager” of the title is Pascal’s Wager, which states that believing in God is the most rational course of action when the potential benefits—eternal life in heaven—far outweigh the passing pleasures that belief asks us to sacrifice. Helen Holmes, who makes Marya’s acquaintance by shouting at her to get out of the way of her motorized wheelchair, stands much in need of reform at the story’s outset. Surrounded by greedy, grasping relatives, she plans to give most of her money away and enjoy the rest for whatever time she has left. Of course, someone out there has other plans. Will Helen’s wager pay off? And will the “purple pest” solve the crime before she runs out of tea and digestive biscuits?

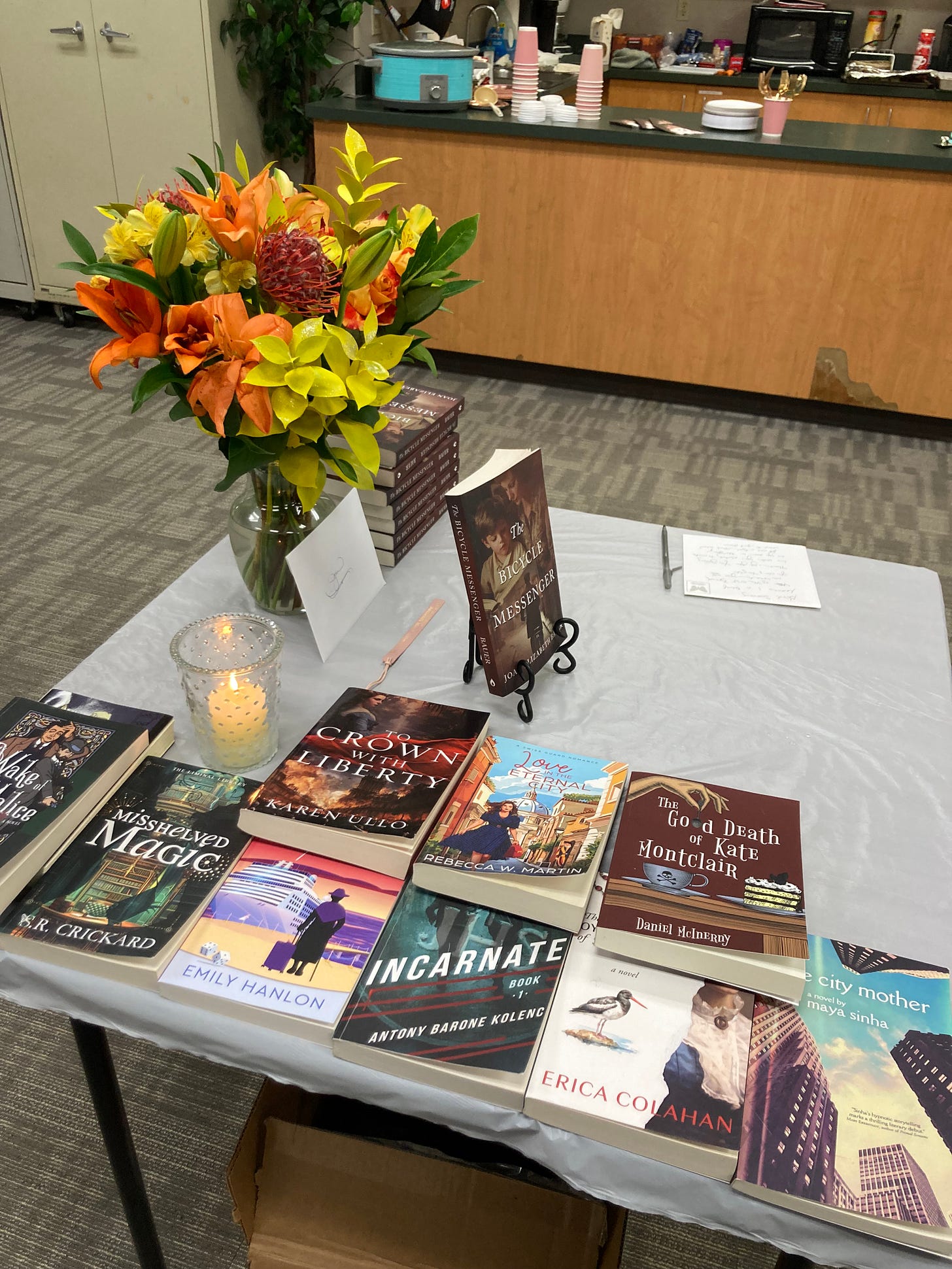

This is a wonderfully funny book in which the characters are all marked by idiosyncratic bits of business. Whenever someone needs advice, Marya roots in her lilac and orange plaid bag for a laminated index card with an appropriate scripture quote. Two detectives who appear to be in love banter back and forth as to which era featured the most luminaries—the Middle Ages or the Renaissance. Martha’s opponent in the race for police commissioner plays dirty tricks, while a handsome childhood friend takes Martha’s side. I haven’t yet read the previous two entries in the series, but I had no trouble settling in. Emily Hanlon is a pro, and I highly recommend this funny Catholic read.

Unfortunately, all good things must come to an end, including delightful books and trips to Florida in December. Our flight home was delayed, and when we finally deplaned in Milwaukee well after midnight, I saw my breath in the jetway—the temperature had dropped to the low single digits. As we hurried coatless to our car in the parking garage, I understood what is meant by the phrase “piercing cold” in the St. Andrew novena. I’ve grown to love this little prayer as I say it over and over throughout the day:

Hail and blessed be the hour and moment in which the Son of God was born of the most pure Virgin Mary, at midnight, in Bethlehem, in the piercing cold. In that hour vouchsafe, I beseech Thee, O my God, to hear my prayer and grant my desires, through the merits of Our Savior Jesus Christ, and of His blessed Mother. Amen.

Come, Lord Jesus! A blessed Advent to all!

*As of this writing, a brief thaw and chilly rain have uncovered sections of grass and made the sidewalks so slippery as to be nearly impassable. The exhaust-blackened snow lining the streets is receding to reveal the last of November’s uncollected leaves. Ah, Milwaukee! We’ll hope for more snow.